Why do we all go left in a westerly anyways?

The sun is shining on a warm mid-July weekend morning. The air on English Bay is crystal clear with no hint of haze over Vancouver Island. Some puffy white clouds are starting to form in the east over the valley. You launch your Martin 242, crew bright eyed and ready to race. A dark wind line is already visible in the west promising another great day of racing in a westerly thermal breeze on English bay.Fresh from re-reading your favourite racing tactics book last night you resolve to take some of the lessons to heart this time out. Foremost - one of the golden rules of sailboat racing – stay in the middle of the course! The logic makes sense. Avoid the laylines at all costs until a few boatlengths to the rounding. It’s difficult to accurately call the layline from far out, so you’re likely to be either overstood or understood at the mark. Even if you manage to optimally tack just a bit below layline sailing upwind, there are very few tactical options once you’re in a corner. In a header boats to leeward will gain and you can’t tack onto the lifted tack anymore because you’re too close to the layline. In a lift you are overstood, so again any boats to leeward will gain because you sailed too much distance by going outside the layline. To make matters worse, if you’re near the port layline rounding the mark in potential sea of boats on the starboard layline will be a nightmare.

You get a great first start in a building westerly, and you elect to initially stay with the pack as they all charge towards the port layline. Several boats overstand the layline by several lengths. The lead boat tacked a bit early and looks to be just below the port layline, but they elect to tack and cover the boats further to the left and overstand with them, surely pure madness! With the wise words of Stuart Walker still ringing in your ears you make a conservative tack well before the layline to stay closer to the middle of the course, keeping your tactical options open. Three quarters of the way up the beat, and much to your chagrin, every boat to the left of you has come screaming down over top of you on a close reach, burying you to yet another mid-pack weather mark rounding. Where did it all go so wrong?

Welcome to the English Bay Westerly. So why do we do it?

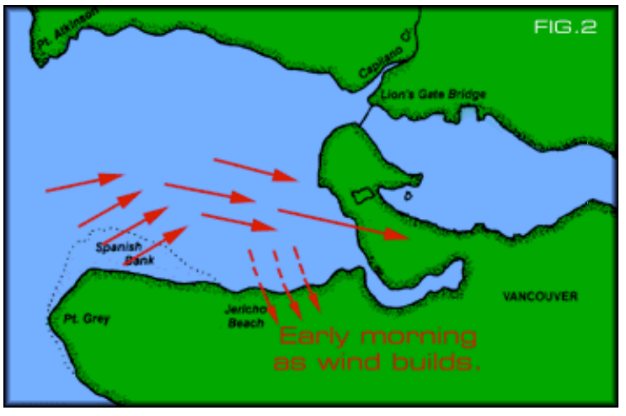

Check out Figure 2, below (where’s Figure 1, you ask? Don’t ask.) The westerly thermal breeze tends to fill in in the late morning at around 11 am. It will consistently increase until it hits its maximum for the day at around 2:30 pm. As it fills, it tends to bend onto the south shore. Later in the day, after thermal heating, it will blow more directly down the bay. As the wind builds there may be temporary oscillating shifts but once filled in, the direction seems relatively stable.

So 2 important things:

- As the westerly first fills in, there will often be a big left shift. Left shift = go left. Plus there’s often a distinct line of pressure filling in from the west. It’s always best to be first to the new breeze. New breeze to the left = go left.

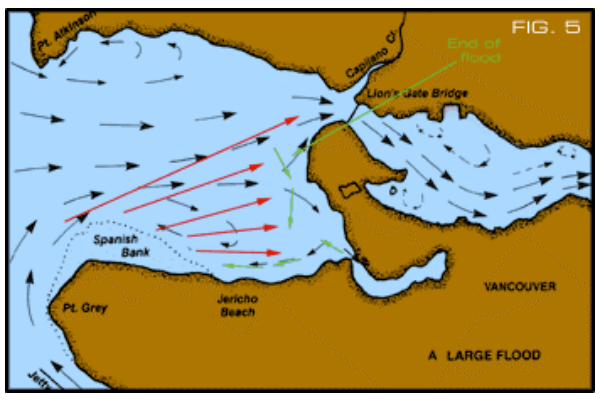

- Because of the geography of the shoreline to the south, there is also a persistent geographical back (left shift) as you sail west up the bay, even after the breeze is established. The amount of this back from the leeward to the windward mark can be in the order of 10-15 degrees. Again left shift = go left.

So what happens in the English Bay westerly is the typical “low risk” strategy of avoiding the corners is reversed. It’s often much lower risk to well overstand the port layline, usually the further left you can get, the further ahead you’ll be at the weather mark. Because of this; there are few to no 'passing lanes' so starts and boat speed are at a major premium in a westerly. It often pays to start near the pin even if the boat is favoured by as much as a length or two!

Some Exceptions!

- Late in the day, say around 7-8PM as you’re starting the second beat of the second Wednesday night race, I find the dying westerly sometimes “pumps” north before completely dying. If you’re playing the left as usual one or two boats that decide to take a flyer to the right side of the course can sometimes come out way ahead. The problem is, catching this final shift is Very Tricky, and it’s only sometimes.

- If the westerly is not fully established, or if it’s a non-thermal (system generated) westerly (characterized by more cloudy/overcast or clearing weather), the wind may be more shifty than in a “regular” westerly. It still often pays to go left especially in any kind of flood, but there’s more likely to be a few right shifts that can benefit boats sticking closer to the center of the course.

- One of the few times you can revert to more ‘standard’ racing strategy and make it work in a normal westerly is in a strong ebb, especially out in the middle of the bay away from the south shore. The progressive geographic shift is still a factor, but a strong ebb current can mean an early tack to port even well before the layline can pay off.

Credit: this article draws heavily on the descriptions of Winds and Tides on English Bay originally developed for the 1997 J/24 Canadian Championship at RVYC. Content by Claire Adams, former head instructor at RVYC, with assistance by Past Commodore Don Martin and Peter Chandler from the Institute of Ocean Sciences in Victoria. The graphics were provided courtesy of AREA51 Interactive, a website design company in Vancouver.